On the occasion of 遥か LONGE, CAAA Guimarães

May 2022

Text by Ana Paisano

The Japanese term haruka (遥か: far away, distant) denotes a distance that is not merely physical, but also temporal; memories of times and places long lost. During her four years in Japan, Filipa Tojal searched for the unfamiliar and the undefined, driven by a desire to move far, away from her place of origin. Her personal journey started from a sincere appreciation of the pictorial universe of painting, before gradually transforming itself into a poetic and meditative trajectory, driven by curiosity, and a deep sense of cultural sensitivity. Using mostly traditional techniques, she explored concepts such as the imperfect, the incomplete and the impermanent, that are inextricably connected with the culture and nature of the Japanese islands.

Filipa’s early work had revolved around natural landscapes, focusing on the rugged peaks of her home country, Portugal. Thus, arriving in this new place in East Asia, she set out once again to understand the mountains, and their connection to the land that they rose from. Japan is an archipelago that stretches beyond the eastern edge of Eurasia; isolated from the mainland through the East Japan Sea, it is the last major landmass before the endless expanse of the Pacific Ocean. It is topographically unique, covered in densely forested mountains that lie along an active fault line. The steep, evolving landscape, stretches from the subarctic north-east to a subtropical south-west, possessing myriad gradations and seasonal shifts. Filipa introduced these natural shifts into her work, in an attempt to create a sense of intimacy with the landscape.

Her paintings often feature large expanses of white opaqueness, but the white does not signify emptiness: it has an atmospheric weight, like a cloud of mist, implying a different reality hidden beyond, that our imagination strives to fill. The concept of Ma (間) in Japanese philosophy states that “form is emptiness, emptiness is form”, emptiness creates space for possibility. It engages the imagination and invites the viewer to inhabit it, consciously or unconsciously — sharp mountaintops, and pine groves grazing the edge of the sea might be hiding right behind this haze; an unimaginable spectacle shaped by earth, water and wind. The rough, textured brushwork used to represent the Japanese landscape, moors us to its reality, while our eyes float away into the misty, blank space, enveloped by a soothing silence. The aim of these paintings and objets d’art is not figurative, but evocative: a means through which one can speculate about the world and stir up fading memories. Like the names of traditional Japanese hues, which try to capture fleeting moments as subtle as the sparkle of wet moss, Filipa’s works seek to convey a perpetually moving vagueness, a play of mist and light, colour and texture; the traces of her own memories.

After arriving in Japan, Filipa became fascinated with natural pigments, and their effect on the painting process itself, which is reflected on her works as well as her daily life full of small rituals: boiling water, grinding pigments, preparing surfaces, sitting on their edges and, painting. She gradually abandoned the use of acrylic and oil paints, preferring instead the slow, dedicated method of layering these natural, and naturally imperfect mineral and oral dyes on hand woven cotton and linen, or Japanese washi paper. Traditional natural binders of animal origin have been replaced by other natural materials, such as rice or seaweed. Through these materials, the Japanese landscape grows into an actual part of the painting, interwoven into its materiality and texture. Many of the techniques that Filipa employs have been meticulously passed down through centuries of craftspeople and artisans; yet throughout her technical and visual research, she combines, alters and explores them in contemporary ways, firmly placing her works within the context of a continually evolving Japanese cultural tradition.

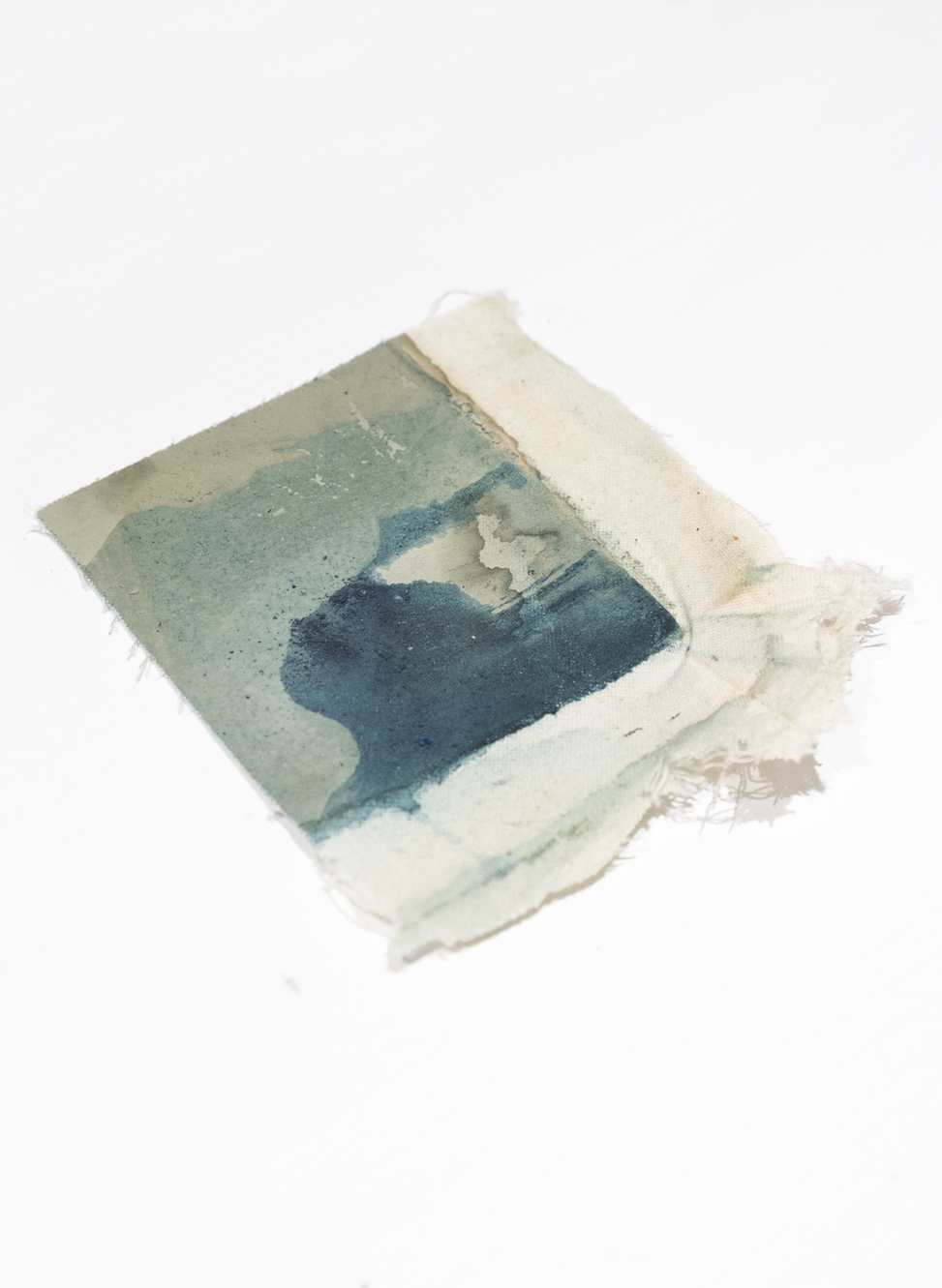

The works in this exhibition comprise a variety of paintings on paper and fabric as well as objects that Filipa collected during her trips, such as Japanese books and tatami fragments, still reverberating with the echoes of quotidian realities that they were once part of. These objects are appropriated, transformed, painted on, and intuitively arranged on the floor, walls and plinths. They act as interlocutors to the paintings, and as intermediaries, inviting the observer to ramble and wander, perhaps reflecting on the seasonal cycles of nature. Small details and intricacies carry on this dialogue: the woven surfaces, the brushwork gestures, and natural aggregates discreetly appearing within the pigments. The hues echo the wet earth, green leaves and pale mists, glow with vibrant greens and emeralds, before they sink into the earthy tones of ochre and the golden brown of tatami. A chromatic landscape that is in slow transformation itself, as its natural materials gradually age and evolve, carrying with it the murmurs and sensibilities of the mountains.

The exhibition is organized in two spaces: the atelier room and the tatami room. These two rooms and the itinerary between them, form an intimate invitation into Filipa’s process of artistic work. The tatami room is a sitting and meditation installation — a protected space where we take off our shoes to enter, following the Japanese ritual of entering a home, or a teahouse. A few carefully chosen objects are laid out in a way that emphasizes the empty space around them, the smooth lines and clean surfaces. The atelier room is akin to an archaeological site, where several objects, constructions and paintings are exposed and counterposed to each other. The paintings are arranged on the walls, while the two islands (plinths) display elements of Filipa’s painting process, but also a collection of visual references, memories, photographic records and travel diaries.

Ana Paisano

On the occasion of VERDANT, Sage Culture

November 2021

Text by Filipa Tojal, Marina Figueiredo and Nicholas Alonso

"The imaginary of my works comes from everywhere, not only the villages I grew up in. The Portuguese mountainside, the dryness of its soil, the calming rivers appear as much as the Japanese greenery in its fullness, the Northern Vietnamese lakes, as well as the wintery city gardens, like Berlin's. Sometimes the first lines come from a specific place and end up somewhere else, but mostly, it is a composition of different instances in a new atmospheric reality. While traveling, I draw, paint and collect travel diaries - but once I start a painting, each canvas starts empty, without anticipation of what will appear, hence the persistence of my practice." FT

About the exhibition

"Verdant" presents the artist's most recent work, which traces her return to her home country, Portugal, after four years living in Japan. The exhibition brings together several paintings completed in her studio, a charming centenary house in the streets of Porto. While this painting selection is undeniably abstract, they also suggest the artist's natural sceneries, which inhabit her mind and memories. In the last years, influenced by the time spent in Japan and the Japanese way of painting, Filipa Tojal searched for natural and raw surfaces like paper, textiles, other fibers, and botanical dyes or mineral pigments. The works featured in this exhibition surround matters like tradition and heritage, as most of the surfaces used are the linens passed through generations of the artist's family. Closely, each painting and surface is subtly raw in its textures, and its even colors do not cause distraction from the material, its meaning, and its substance. Each painting carries an intimate and honest relationship between the pigments, the weave of the linens, and the natural elements that wander through it. The green in hue or in freshness and the gestures and rhythms of the compositions naturally makes you wonder about landscapes - forests, lakes, or seashores, being somewhere specific for the artist or the observer, or nowhere at all. The ultimate sense of Verdant, a spacious conversation of small to big scale paintings, is to be invited to stillness. The title recalls a fresh atmosphere of infinite greens and the poetic cycle of nature, growth, and life.

The title "Verdant" can also reminisce about the simple Japanese word 新緑 Shinryoku, meaning "new green" or "the fresh verdure of spring." This concept conveys a specific season where sprouts and new branches appear in trees and vegetation during springtime. This new fresh tone of green can be easily spotted, even in the far distance, in every forest, mountain, or garden. Despite its small area, Japan is one of the most forested countries in the world. Its very favorable geological and climatic environment forms abundant woodlands, making it 70% of its total land. Filipa has treated nature as her subject matter, bringing this subject into the proximity of our lives, undeniably taking in uence from the Japanese sense and harmonious relationship with nature. Both Shinryoku and Verdant suggest the visual and contemplative side of each painting and the overall feel of the exhibition. Still, both words can also mirror the artist's growth after a period of reflection and introspection – just as spring after winter. Filipa Tojal has traveled and shared her journey of four years dedicated to Japan, driven by the aspiration of moving away from the place of origin, almost acting with the same understanding of Jean François Lyotard that "In order to have a feel for landscape you have to lose your feeling of place." Filipa left Japan in 2020, and these are the first significant body of works completed after such an extensive and reflective experience in the East. This new translation of unique experiences of nature combines Eastern sensitivity and Western materiality. Visitors are invited to observe every detail, pigments, the weave of the surface, the gesture, and the natural elements that appear discreetly in each painting.

Since her experience in Japan, Filipa has been fascinated by pigments and the cooking performance of the painting process. For that, she hasn't been using paint tubes, preferring, instead, the slowly and dedicated method of grinding, mixing, blending, and finding the textures and irregularities that she so appreciates in her final works. Culturally significant, most of these paintings are made using hand-woven textiles that, from plant fibers, speak about Portuguese soil, its true origin. While "Stream" and "Verde-linho" are fullfilled with the energy of floating water and immersion, "Home country" clearly portrays land and the movement of vegetation. Together with "Sliding," these small-scale pieces are made using different types of linen fabric, some stronger, some finer. In "Verde-linho," the weave and substance of the linen are so strong that you can almost feel the whole cycle of the material - its plantation, harvesting, and weaving."Sliding" is compact and concerned about its limit. Two vertical lines sli- ding down. The gravitational force of nature and the force of that brushstroke trying to t in the limit of the stretcher. "Riverbank" is textured and washed away, so are "Return" and "Temporary Changes." Each brushwork is tense and fighting the other, just as the water streams between the river margins.

Layers and layers of soft watery colors bring together an unpredictable and self-isolated image of what can be soil, sky, or water. It is natural for the artist to walk around and to collect – to bring home some objects, being them stones, leaves, twigs, moss:

"As they are placed in a minimal studio next to the pigments, mixing them up came naturally. Without reducing them to powder, they appear in the linen as a surprise but not unexpected. They belong to those tones - to that reality - and its appearance just comes as a confirmation that we are indeed facing a landscape, and a personal experience of nature.

In Japan, I observed and experienced a lot of papermaking and other craft processes, and when I came back to Portugal, I looked at these linens using the same filter. It was clear to me how the paper- making tools like sukibune and suketa were just like the handlooms. I was drawn to the heavyweight, strong quality of these linens and how they needed to be entrenched with pigments as well as landscapes."

In my family, in everyone's house, there were always drawers or trunks lled with these fabrics, which, for me, always smelled like stone houses and olive trees. Opening these trunks connected me to the women in my family I have never had the chance to meet and the straw beds I never slept in. Some of these had delicate embroideries, but most of them were just plain and simple. They were the bed sheets everyone slept on every day. From mother to daughter, these linens passed by, generation by generation." FT

On the occasion of THE TREES ARE ALL SINGING, Casa das Artes do Porto

(Organized by Sismógrafo)

June 2019

Text by Óscar Faria

You redden like the dawn and you burn: flame of the Sun

Hildegard of Bingen was a Benedictine nun who lived in the twelfth century. Mystic, theologian, visionary, this woman is considered by many simultaneously the first biologist, physician and feminist. She also left us writings that cover countless disciplines: from poetry to music, and also the healing properties of plants. One of the notions she worked on was that of “Viriditas”, that vital force visible in the green color that comes from the leaves of the trees, herbs, moss and some vegetables. As the Rhine sibyl notes: “Glance at the sun. See the moon and the stars. Gaze at the beauty of earth’s greenings. Now, think”.

The Rhenish nun further states that this green, verdant energy, coming from eternity, was responsible both for sprouting the plants and fo the spiritual development of the human being. It is therefore, as Audrey Fella refers (Hildegarde de Bingen. Corps et âme en Dieu, Points: Paris, 2015), a divine operation, that of the "greening force", a quality that manifests itself through the ascending greenery of the earth that incorporates itself in each individual. In one of the "Canticles of Ecstasy" written by Hildegard there is the responsory "O nobilissima viriditas", where we can read: “O most honored Greening Force,/ You who roots in the Sun;/ You who lights up, in shining serenity, within a wheel/ that earthly excellence fails to comprehend./You are enfolded/ in the weaving of divine mysteries./ You redden like the dawn/ and you burn: flame of the Sun.”

The exhibition by Filipa Tojal is covered by this “greening force” to which Hildegard of Bingen refers. Currently living in Japan, the artist translates in her works a unique experience of nature. Each painting embraces the landscape, giving us back this gesture in a silent way: in its abstract forms it is almost possible to hear the rustle of leaves blown by the wind, to glimpse in them the manifestation of the sun, the touch of an insect or the virtues of water. It is also plausible to realize the plastic quality of these works, sometimes miniatures, which echo the verbs invade, dye and overlap. There is also an aesthetics of the fragment that crosses this exhibition, apparently emerging from an archeology of the landscape through which the artist gleans mainly colors, movements and tensions, such as climate changes. The nature presented by Filipa Tojal thus mirrors the surrounding nature, with its mutations. And vice versa. Here, there is a phenomenology that brings these works closer to others performed by an artist that has made the landscape the main theme of his practice: João Queiroz, who will also be present in this cycle of exhibitions, in Casa das Artes.

In the domain of correspondences, the fragments of Filipa Tojal, which appear to our eyes as finished work, may be associated with rags or pottery shards. This dimension can lead us to a poem by Sappho of Lesbos or to a Roman piece on terra sigillata, although in case you want to underline the green vigor that underlies this exhibition, you can instead summon examples from contemporary American poetry - Gary Snyder, W. S. Merwin- or from the green-manganese pottery production of the Madinatal palace - Zahra (10th century) - green is for the Arab people the color of happiness. There is another question, related to Art History, that can be raised when looking at this set of paintings on paper and on fabric: Do they owe something to Impressionism? The answer will certainly not be a simple one, especially at a time when the past is absorbed almost immediately by the present, thus preventing an art form from having time for maturing. However, an approximation between the work of Filipa Tojal and this movement that emerged in the nineteenth century can be productive, taking, for example, as model the work of Berthe Morisot and her "unfinished" works.

The French painter and the "unfinished" style visible in many of her works open a series of bridges to some contemporary artistic practices. Curiously, this dimension of "perpetual resumption" is found in works that have as their subject landscapes, trees, gardens, as if nature could never be captured in a painting, in a drawing or in a watercolor, which only constitute approximations to the real. We are dealing here with the "floating charm of the sketch", as it is said in a commentary at the end of the nineteenth century. Unfinished, fragmented, sketched. If, on the one hand, we can find these characteristics in the work of Filipa Tojal, on the other hand, their opposite is also true. The artist's work is finished, definitive, without any doubt regarding its position in the world. It’s up to us, spectators, to solve the puzzle, the enigma. It is up to each one of us to find the answer to these little pieces of nature, of art, made with pigments on Japanese paper, raw fabric and paper.

"The trees all singing", title of the exhibition, is a verse by Gary Snyder, poet and advocate of a deep ecology. "The trees all singing." Shown on structures specially designed for the occasion, the works of Filipa Tojal are an invitation to meditation, to silence, to a reunion with this “greening force” present in nature and in every human being. This may also be the opportunity to discover the tulip tree of Virginia, this tree planted more than a hundred years ago in the gardens of the Palace of the 3rd Viscount of Vilar d'Allen, which is 32 meters high and 30 meters in diameter. And embrace it, as we embrace the paintings, which, like leaves, fall on our eyes:

“The trees we climb and the ground we walk on have given us five fingers and toes. The ‘place’ (from the toot plat, broad, spreading, flat) gave us far-seeing eyes, the streams and breezes gave us versatile tongues and whorly ears. The land gave us a stride, and the lake a dive. The amazement gave us our kind of mind. We should be thankful for that, and take nature's stricter lessons with some grace” (Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild, San Francisco, North Point Press, 1990, p. 29).

In terms of setting-up, it is noteworthy that the "funaria hygrometrica" or "common moss" served as a model for the installation of works in the space. For, this tiny plant, in addition to preferring uncovered terrains, well exposed to the sun, is frequently the pioneer of vegetation on bare soils, often found in places that have burned. Laid in the structures designed by the artist, the paintings appear as a metaphor of a nature always in renewal: the most noble greening force of a planet in crisis.

Óscar Faria